Perhaps your actuarial models just aren’t satisfying your needs, because they take too long to run. Or you feel like there is too much skepticism from your audience when you present results, and you find yourself defending every little decision for far longer than you think you should.

These types of problems are indicative that your model is not optimized for your use. A logical question might therefore be, How can we optimize our models?

Instinctively, you might think you could just throw some faster processors at it, maybe make a data translation macro, or issue another memo about how everyone has to be better at documentation, and you’ll just magically get there.

However, not all problems are solved equally. Actuarial model optimization should be considered the last step in building and implementing effective models, because some of those problems are structural, rather than being based on inefficient performance.

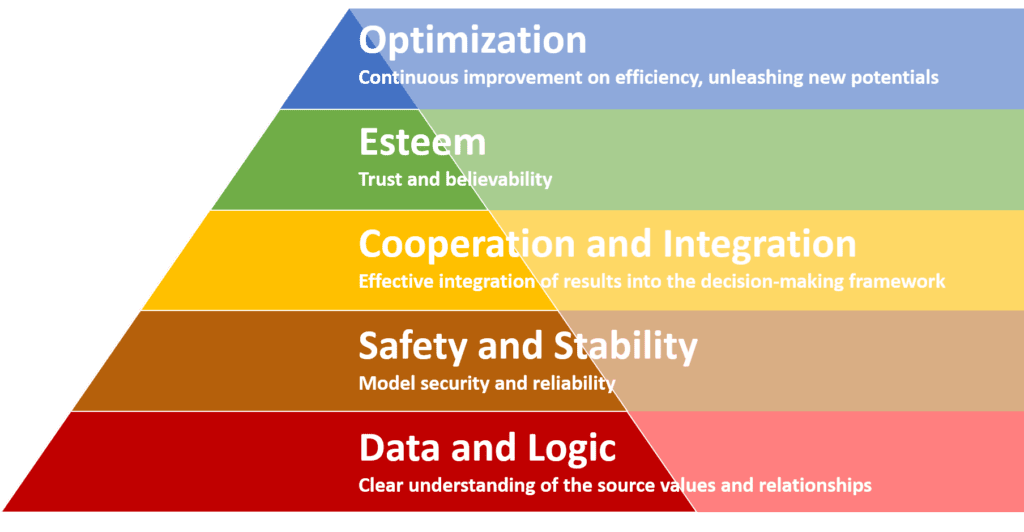

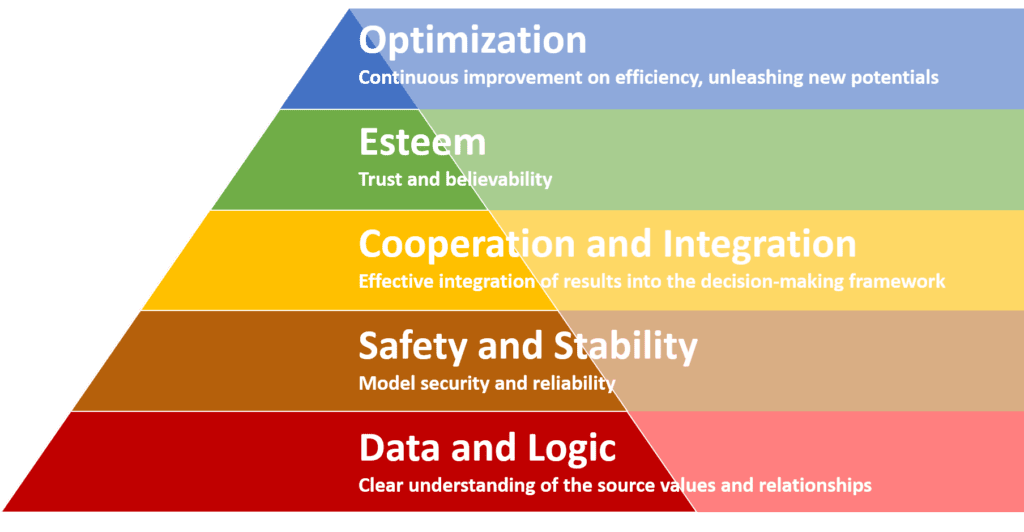

So how should you think about prioritizing model improvements? We suggest applying a model optimization hierarchy.

Hierarchies in the real world

You’ve heard of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. This framework, introduced in the 1950s, describes how humans have certain categories of need which, when fulfilled, generally allow for access to the next level. When they are not fulfilled, moving upwards in the hierarchy is made more difficult, if not significantly limited.

Here’s a graphic representation of the various levels Maslow proposed:

Under Maslow’s hierarchy, lower level needs, such as sustenance needs like air, water, food, and shelter, must be fulfilled before proper consideration can be given to the next levels of need. This creates a structure for personal development, as well as a framework that allows for investigation of dissatisfaction in an individual’s life.

Might there be a similar hierarchy of needs for actuarial models? Let’s look at each of the levels individually.

Physiological needs

For humans, this is the basic building blocks, the very fundamental elements that we need to live: air, water, food, shelter, and so on.

What would the parallel be in an actuarial model? Most simply, it’s the fundamental elements that we would use in building any kind of model: data tables, formulas, input/output relationships, and so on.

Without some formula for relating inputs to outputs, there is no model. Without some kind of data set to be input into that model, there is nothing to be calculated. At the most basic level, these would be the fundamental building blocks of a model, analogous to the air, food, water, and shelter that humans need to survive.

In actuarial models, these blocks are not physiological. Instead, they’re more related to data needs and logic relationships. So we rename that level as Data and Logic.

Safety needs

Personal security needs to be maintained. Human beings desire to know they have some stability (a good job, for example), that they can maintain themselves reasonably well (health and resources in preparation for potential disasters), and can keep out threats.

In the same way, the security and consistency of your model need to be maintained. You need to be able to protect against untoward changes to the underlying (lower-level) data and logic. You need to be able to fairly consistently demonstrate that you not only can keep what’s inside your model from degrading itself or corrupting itself, but that you can also protect against outside influences.

Those internal challenges may be something like accidentally overwriting a data table, or forgetting to link documentation of an assumption change to the actual model run that used those new values.

As such, it sounds pretty reasonable to still call this level Safety and Stability.

Love and belonging

Are you part of a group that you should be part of? Are you respected? Are you valued for your contributions?

It’s much better for the vast majority of people when they have that sense of belonging. There are some other animals such as polar bears and sharks, for example, who live solitary lives. But humans have evolved to be communal beings, and that means we find value in connecting with others.

In Maslow’s Hierarchy, this shows up when we have solid and meaningful connections and relationships amongst family, friends, peers, and business colleagues.

The same happens for our actuarial models. Those models which are “stand-alone” or “one-off” builds generally don’t have the same kind of inclusion in the general model inventory. They are often treated as different or weird, because they don’t fit in to the standard model governance framework. They may not be as trusted or as efficiently employed as they could be, because of this.

The challenge is, then, when results are coming out of those models, the end users (either actuaries or those downstream from them) can become more skeptical of their results.

This is a problem because those one-off systems tend to drift off in their own direction. Rather than getting with the program and “playing nice” with the rest of the models in-force, they can end up with their own data pipelines or governance practices.

As a result, the actuaries end up maintaining more documentation, more work-arounds, and more excess steps to integrate the results of those “exceptional” models back into the larger decision-making framework.

Instead of “love and belonging”, perhaps we rewrite this as Cooperation and Integration. Frankly, it’s kind of hard for models to love without a heart. But they can cooperate and belong as part of your integrated decision-making framework.

Esteem

Esteem shows up in humans when they feel valued. When they are confident in their skills and abilities to enable change in either themselves or the world around them. Again, this is often only accessible when all of the supporting elements of the hierarchy exist.

For your actuarial models, you see “esteem” when people believe the model results on the first pass. They listen when you talk about your confidence intervals, and they know what that means to them. They trust and respect what’s coming out of the models, because they know that the underlying needs have all been satisfied.

Essentially, they look up to you and respect your models because those models have demonstrated over time that they are worthy of that respect.

This one doesn’t need a name change. Models themselves can be considered to have Esteem in the same way as individuals can.

Self-Actualization

Those humans who are self-actualized, at the top of Maslow’s Hierarchy, are the best they can be. And, importantly, they continue to work on themselves to improve themselves and become even better.

The parallel is when your models are “all they can be”. A couple of examples are creating feedback loops that lead to refining error bounds smaller and implementing new technologies to run the same models, only faster.

These models are doing the best they can. Those headaches and frustrations from before are minimized. And, when they do show up from time to time, actuaries familiar with this structure can easily diagnose where the problem is and work to solve it at the right level.

You might even call it Model Actualization or the process of fully realizing the potential inherent within. However, we’ll just stick with Optimization, which we’ll call the continuous process of refinement for better and better results.

Why aren’t all models optimized anyway?

We have countless anecdotes of headaches and frustrations with actuarial models. These headaches and frustrations range across the spectrum, from doing busy-work to using systems that were designed in the 80s and have never been updated since.

Many of the frustrations center around actuaries wanting to do better work, yet still feeling constrained by limitations within the model, the data available, or the time available for analysis.

But why don’t those problems get solved? Part of it may be because there is no formalization of how to approach the multiple shortcomings in the modeling structure. Without some kind of prioritization of which problems to work on first, the whole process becomes ineffective.

When people want to change, they can ask questions about what are the “needs” that are missing from their life. Once they’ve created an inventory of problems, they often start working on the lower-level needs before attempting to resolve higher-level ones.

It doesn’t make a lot of sense (and there isn’t much opportunity!) to be concerned with Self-actualization when Security is lacking. In the same way, trying to optimize a model with poor data processes doesn’t actually solve the problem. Instead, it actually reinforces the bad behavior by obscuring the real problem.

Reframing modeling needs under a hierarchy, then, can be a way to organize your thoughts about how to make your models and your modeling practice better. Using that hierarchy you may be able to develop a clear prioritization of future enhancements.

What does the Model Optimization Hierarchy look like?

If you feel like your models and your modeling output isn’t “all it could be”, perhaps it’s time to evaluate them in light of this hierarchy to find out where the problems lie. Once you pinpoint them, you may have a better chance of correcting them and moving up along the hierarchy.

How do you do that? Begin at the bottom, and ask some questions of your modeling practice, your department, and your company in general. Work your way up, and you should be able to find out where your own specific pain points lie.

Here are some questions you may use to start the evaluation process. We’re sure you could come up with dozens more options.

| Data and Logic | Do we trust the data sources? Do we believe the formulas are correct? Do we understand how the data flows from input through the model to the output? Do we believe the values that have come out? Are they reasonable? If we change inputs (for example, increasing some rate by 10%), do we see changes in outputs? Do those changes make sense in magnitude and direction? |

| Safety and Stability | Do we know who has access to these models? Do we know what vulnerabilities might lie in the process, in the servers, in the results databases? Do we have ways of ensuring that results, once created, aren’t lost, overwritten, or manipulated? Do we have ways to ensure that nobody from outside our organization can access our data sets, formulas, and conclusions? |

| Cooperation and Integration | Are the inputs created in ways that are consistent with other model input creation processes? Are there similar tasks being performed in different models, but in different ways? Are there differences between formulas (that should be performing similar tasks) across models? Are these differences valid and worthy to maintain? Should the model outputs be accessible to other models? Are they? If not, which part should change? Or should all of them be modified to some new structure? |

| Esteem | Do directors and non-actuaries believe you when you present results of a model? Do they ask you to “sharpen your pencil” on your results? (Often this comes from marketing or sales people who don’t think rates are competitive enough, so they start to question your model’s integrity.) Do they ask for external validations? Do they actually take your model findings and implement the recommendations into future actions, or do they delay and push back, asking you to justify once again? |

| Model Optimization | Could this run faster? Could we get less down-time? What technology would we need in order to do that? Could this model be applied to other existing tasks (i.e. creating efficiency)? What additional business questions could this model also provide answers for (i.e. demonstrating robustness)? What new issues or concerns could we approach now that our concerns of this model have been addressed? |

Putting this in practice

When you cycle through these questions and apply them to your various models, you may be able to uncover the cause of dissatisfaction with your models. And to be honest, it may not even be at the level you thought it was. Only by actually asking the questions and performing the evaluation can you find out just what deficiencies exist.

Once identified, you can begin the process of fulfilling any lower-level needs in order to be able to more fully support higher-level needs.

And do note, just like self improvement, you should not assume that it is all-or-nothing to move up to the next level. For example, you might evaluate Data and Logic as having 10 deficiencies, and Safety as having 6.

You don’t need to fully rectify every Data and Logic deficiency before also beginning work on the Safety issues, as long as you have a plan in place. Plus, remember that different models could be in different stages of progression as you move forward.

The important thing is to continually make progress

Just as it is unlikely to ever create the “perfect” human, it is unlikely you will ever create the “perfect” model. But you can always improve. And using a structure like this to evaluate what the needs are can be a good way to prioritize the concerns you are facing every day.

If you’d like to set up some time to discuss your model structures, especially as they relate to your modern actuarial tasks, give us a call or email. We’d be happy to discuss whether modern actuarial software like SLOPE would help you along the path towards model optimization.