Introduction

This guest blog continues the occasional series of advice from other voices to help actuaries improve their mindset, skill set, and career. Today’s article comes courtesy of Bradley Shearer, FIA, CFA, Executive Director of Protagion Active Career Management.

Disclaimer: Slope Software does not officially endorse Mr. Shearer’s position nor his firm. Mr. Shearer’s post on this blog should not be viewed as an endorsement of Slope Software. The conclusions and opinions are his own and should be considered as such.

Deep analogical thinking involves recognising distant analogies, conceptual similarities across domains or scenarios that appear to have little in common on the surface. It takes something new and makes it more familiar, or takes what is familiar and considers it afresh, allowing us to reason through problems we have never seen in unfamiliar contexts.

— bradley shearer —

The Slippery Slope of Specialisation

Actuarial Science is by nature a science, while also being about application of its techniques/approaches to the business world. It’s less about operating at the cutting edge for the sake of extending scientific boundaries, and more about practical application to solve business challenges. Over time, however, I’ve become uneasy about how actuaries tend to focus on our own specialisms, rather than considering the interfaces between disciplines.

The professional consequence is that we as a collective are slow to react and adapt to insights from other domains, even related ones! Two examples, in recent decades, are financial economics and data science. “Back in my day”, to qualify as a fellow, we needed to complete specialist technical studies in all of the available actuarial disciplines then: life insurance, general insurance / property & casualty, pensions/retirement & employee benefits, and investments. I feel this makes me a broader actuary, and has spurred me to work across varied domains over my career so far.

These days though, budding actuaries choose their preferred track from these and more (such as healthcare or enterprise risk management). This makes it possible to focus narrowly on pricing and reserving in purely one discipline i.e. a more specialised breed of actuary.

“…As specialists become more narrowly focused, ‘the box’ is more like Russian nesting dolls. Specialists divide into subspecialities, which soon divide into sub-subspecialities. Even if they get outside the small doll, they may get stuck inside the next, slightly larger one.”

DAVID EPSTEIN in Range

Analysis and Synthesis

Many of our educational frameworks globally are premised on building ‘core’ foundations of skills, followed by layers of application that become more specialised. The distinction between analysis and synthesis is often made (and is a key element of the actuarial way of thinking). And then, post-qualification, we add other skills necessary for the world of business through lifelong learning.

The guild system in Europe arose in the Middle Ages as artisans and merchants sought to maintain and protect specialised skills and trades. Although such guilds often produced highly trained and specialised individuals who perfected their trade through prolonged apprenticeships, they also encouraged conservatism and stifled innovation”.

Scientists ARTURO CASADEVALL and FERRIC FANG comparing the specialist education of professionals to medieval guilds

To me synthesis is about abstraction, and making connections between different components of our knowledge. It helps us understand the deep structural similarities between concepts, and should allow us to transfer our understanding to new situations and different domains flexibly – a fundamental requirement of modern work. Even our ‘traditional’ areas are being increasingly impacted by previously distinct disciplines, such as psychology and behavioural economics, sustainability, and information technology and automation.

Also key to the actuarial mindset, more so than other professions, is our emphasis on the long-term: we think about probabilities of future events, their consequences, and how to mitigate potential adversity. We make long-term decisions for a world we can’t yet fully conceive. Doing this requires big-picture thinking, while also building model approximations to guide our thoughts. We also know (although sometimes need reminding) that one good tool or model is rarely enough in our complex, interconnected and rapidly evolving world – we need to consider multiple perspectives, and be willing to switch tools in unfamiliar situations.

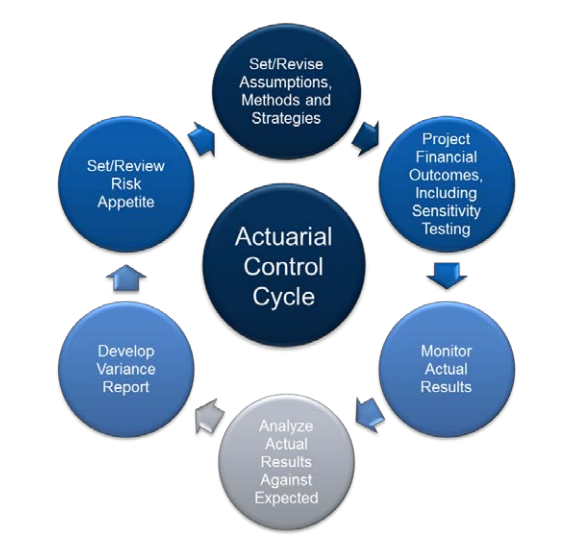

This is easier said than done, especially as some models are ingrained into our culture and part of our domain identities, and often we don’t recognise they are situation-specific tools. We’ve used them over and over in response to the same past challenges and our behaviour has become automatic in our drive for efficiency. The major difficulty, of course, is knowing what situation we’re in at the time and suitably defining the problem we’re looking to solve, as our control cycle reminds us.

Models of the World

Psychologist Robin Hogarth argues that there are two types of environments, with distinct characteristics, each requiring very different actions to optimise learning and maximise success:

- ‘Kind’ ones, where patterns repeat over and over, and feedback is extremely accurate and usually very quick. Examples are chess, golf and classical music: you can improve simply by engaging in an activity and trying to do better. The rules are known and unchanging, and you benefit from observing what happened, attempting to correct your actions, trying again, and repeating the learning cycle until execution is automatic and deviation is minimal i.e. early, hyperspecialised, deliberate practice helps.

- ‘Wicked’ ones, where the rules of the game are often unclear, incomplete or change, there may or may not be recurring patterns, and feedback can be delayed, inaccurate, or both. Multiple moving parts and shifting priorities can add to the complexity. An example is a hospital emergency room (ER), where doctors and nurses are reacting to multiple problems at the same time, with new and possibly conflicting information arriving regularly, and often no feedback on what happened to a patient after their encounter.

Specialists (with years of practice) do very well in kind environments, where the goal is to re-create prior performance as efficiently as possible, given the clearly defined rules. One medical example is a specialised surgeon: for the same scheduled procedure, they improve with repetition, working faster and making fewer mistakes. David Epstein, scientific journalist, expands in his book Range: “If you need to have surgery, you want a doctor who specialises in the procedure and has done it many times, preferably with the same team… They’ve been there, many times, and now have to re-create a well-understood process that they have executed successfully before. The same goes for airline crews. Teams that have experience working together become exceedingly efficient at delegating all of the well-understood tasks required to ensure a smooth flight.”

The challenge comes when the unexpected arises. Hyperspecialist expertise in a narrow area doesn’t magically extend to wicked problems: well-understood processes and techniques may not fit the realities of the new situation. Our models can break down. More uncertainty requires more breadth, in order to cope with (and thrive in) unexpected conditions. Being able to transfer our knowledge and skills across domains means we’re better positioned to adapt to change in a wicked world where work next year might not look like work last year. Sound familiar?

In wicked environments, professionals need to find ways to develop beyond simply reacting, and to assimilate learnings wider than their own direct experiences – this is why ER and other medical professionals, for example, are required to perform reflective practice, an important element of continuing professional development. Actuaries should perform professional reflection too.

Expertise

As alluded to earlier, actuaries make probabilistic forecasts, and we pride ourselves in “making financial sense of the future”. To that extent we are “forecasters”. Philip Tetlock, psychologist and political scientist, and author of Superforecasting, has researched how effective the forecasts of experts are. He found that experts’ predictions become worse as they gather more information “supporting” their mental models of the world. That is, they become more entrenched in their big idea even in the face of contrary facts. Concentrating on the minutiae of an issue within our specialism can lead us to cherry-pick details of a situation that fit and reinforce our unifying theories.

The experts’ areas of speciality, years of experience, academic qualifications, and even (for some) access to classified information, made no difference to the accuracy of their forecasts. When they opined that a future event was impossible or nearly impossible, it still occurred 15% of the time, and when they adamantly declared it would definitely happen, it didn’t more than a quarter of the time!

Many experts never admitted systematic flaws in their judgement, even when the results were known: success was fully because of their own expertise, and defeats were bad luck and near misses, even if wildly wrong. Highly-credentialed experts can become so narrow-minded that they get worse as they gain experience, while dangerously becoming even more confident. Since expertise involves instinctively recognising familiar patterns, it can breed overconfidence, even in wicked environments.

While focused technical experts who avoid overconfidence will always be needed, their work is becoming more widely accessible, so fewer will suffice in each location i.e. greater competition globally. Remote working and international communication technology mean that the insights of hyperspecialists everywhere can be accessed quickly and shared widely with those who then work on business applications of their ideas e.g. how management consultants tap the knowledge of specialists for their projects. More connection of concepts across contexts is needed, integrating international ideas and applying them to new situations, disciplines and challenges – especially in growing sectors outside our traditional industries.

Focused experts also run the risks of obsolescence and disruption from automation as the world changes: the more defined and repetitive a challenge, the more likely it will be automated.

I’m heartened that the actuarial profession is again talking publicly about systemic challenges the world faces. The Global Financial Crisis is often cited as a past example, where overspecialised groups were each optimising their own actions, overseen by narrowly specialised regulators, but together it created a catastrophic collective tragedy. By their nature, systemic issues are complex and interconnected, often ambiguous and uncertain, which is why there are no easy solutions. They require broad, big-picture understanding and a long-term perspective to problem-solving.

Problem-Solving

Because pattern recognition works when facing repeated problems, we can solve these problems using specialists from a single domain, with solutions that worked for them before. But, these break down when facing different challenges. Techniques that can aid us in problem-solving, particularly in a wicked world, include abstraction, decomposition and analogies.

Abstraction involves separating ourselves from the specifics of the problem (the surface) and using an alternative perspective to consider how different elements relate to one another – decomposition of a challenge into component parts can help with this too. The more contexts in which something is learned, the more you can create abstract models and conceptual connections, and the less you rely on any particular example.

This makes you better at applying knowledge to new situations as breadth of training predicts breadth of transfer. We like to see ourselves as professional problem-solvers, but do we really think across domains?

I cherish more than anything else the analogies, my most trustworthy masters. They know all the secrets of nature… One should make great use of them.

JOHANNES KEPLER, astronomer who discovered the laws of planetary motion

Deep analogical thinking involves recognising distant analogies, conceptual similarities across domains or scenarios that appear to have little in common on the surface. It takes something new and makes it more familiar, or takes what is familiar and considers it afresh, allowing us to reason through problems we have never seen in unfamiliar contexts. It is counterintuitive to experts though because it requires us to ignore surface, domain-specific features. Like Kepler, we need to keep pushing for alternative analogies, thinking from multiple perspectives, and seeking deep structural similarities. It is dangerous to draw only on the first analogy, framing the problem in the format most familiar to us. This tendency of problem solvers to employ only familiar methods even though better or more appropriate methods exist is known as the Einstellung effect: previous experience can have a negative effect.

Increasing specialisation actually creates new opportunities for outsiders, who are regularly able to reframe a problem in a way that unlocks a solution i.e. the lack of domain expertise can be an advantage. Think about how often this lack is used as a criticism levelled at data scientists, for example. However, subject matter newbies are far less likely to be blinded by experience, or discount solutions ‘tried before’ or ‘that will never work’. In reality, diversity of experience makes a problem-solving team stronger, as they try new options far more often.

Which brings us back to how crucial it is to define the problem we’re trying to solve. In David Epstein’s words: “Whether chemists, physicists, or political scientists, the most successful problem solvers spend mental energy figuring out what type of problem they are facing before matching a strategy to it, rather than jumping in with memorised procedures.” This ability to determine the deep structure of a problem before attempting to match the right strategy to it is key. Better forecasters, for example, generate lists of separate events with deep structural similarities rather than focusing only on the internal specifics of the event itself – this coaxes them to think like a statistician. And, they analyse their prediction results to uncover lessons, especially for failed predictions – this feedback loop helps make a wicked environment more kind.

Technological progress has impacted problem-solving too, demonstrating the value of blending computers’ and humans’ skills. This involves combining computers’ tactical prowess with human big-picture, strategic thinking and our ability to integrate broadly. From chess to strategy computer games and more, humans can assess the situation and determine what needs further examination, delegating this to computers to investigate and analyse speedily. Like a corporate executive, humans can help synthesise all the tactical analysis into an overall strategy.

One actuarial example of this, prompted by Craig Turnbull’s A History of British Actuarial Thought, is the evolution of the General Insurance industry – at different stages for different lines of business. In the early days, the professional judgement of underwriters was heavily relied on as there was too little data to analyse – they determined what the right questions to ask were. As data was gathered, it was analysed statistically by actuaries to improve predictions. Over time, however, technology now performs much of the analysis and offers recommendations, shifting the need for and roles of actuaries and underwriters.

Variability

As the world becomes more specialised, in our quest for hyperefficiency, defined processes and narrow ranges of outcomes, have we reduced variability too much? The enterprise risk managers among us will know that risk includes upside risk, and that in order to remove the downside, we must sacrifice upside potential (and dampen our long-run at the same time). Safe in the short-term might mean we miss our goals in the long-term. While managing our risk of ruin, we do want to take good risks.

Breakthroughs are high variance. Creativity is hard and inconsistent. Original thinkers fail a lot, but they also succeed wildly. And, going where no-one has before is a very wicked problem as there is no map to follow. Don’t we need to be taking (calculated) risks in order to build the future we want?

Biodiversity

I believe we need both vertical thinkers and lateral thinkers for a thriving profession – we need diversity of thought and diversity of experience. There are a number of natural analogies for this.

The first is from Freeman Dyson, physicist and mathematician, who argued that both focused frogs and visionary birds are needed. “Birds fly high in the air and survey broad vistas of mathematics out to the far horizon. They delight in concepts that unify our thinking and bring together diverse problems from different parts of the landscape. Frogs live in the mud below and see only the flowers that grow nearby. They delight in the details of particular objects, and they solve problems one at a time.”

He saw himself as a frog, but stated: “It is stupid to claim that birds are better than frogs because they see farther, or that frogs are better than birds because they see deeper.” The world, he explained, is both broad and deep, and “we need birds and frogs working together to explore it”.

Another example emphasising the importance of biodiversity comes from Isaiah Berlin, a philosopher, built upon by Philip Tetlock, the psychologist and political scientist we met earlier. Their landscape consisted of narrow-view hedgehogs who know one big thing (deep but narrow), and integrator foxes who know many little things. Tetlock wrote that hedgehogs toil devotedly within one tradition of their specialty while foxes draw from an eclectic array of traditions, accepting ambiguity and contradiction.

Foxes range outside a single discipline or theory, collecting perspectives, learning hungrily from specialists, and integrating facts. Hedgehogs are the ones to produce crucial knowledge. Underneath complexity, hedgehogs see simple rules of cause and effect framed by their own area of expertise, including repeating patterns. In yet another not-so-natural analogy, Tetlock described foxes as having dragonfly eyes made up of tens of thousands of lenses, each with a different perspective, which are then synthesised in the brain.

Just as generalists learn hungrily from specialists, different specialists can cooperate to compensate for areas where they are less knowledgeable. It’s also important to consider the boundaries and interfaces with other systems, as you can discover new ideas there. Scientist Arturo Casadevall describes the dangers of specialists’ “system of parallel trenches” – he warns that everyone is so busy digging deeper into their own trench and rarely standing up to look in the ones next to them, even though the solution to their problem can reside in those trenches.

Conclusion

To wrap up this article on professional specialisation, viewed with an actuarial slant, my challenge to my fellow professionals is to think broader and wider. We should push boundaries and set the rules, rather than simply being rule-takers. We should work to define and shape the world around us, particularly outside of our traditional domains, perhaps acting as ‘revolutionaries’ in ones like space exploration or electric vehicles or…

I encourage you to apply our frameworks and paradigms to other industries, like analogies, especially where there may be deep structural similarities we haven’t yet considered. Integrating and synthesising will allow us to multiply the positive impact we can have on the world. After all, the future is where we’ll make history. Here’s to our professional future!

Bradley Shearer is Executive Director of Protagion Active Career Management, an online consultancy supporting professionals to manage our careers through guidance, mentoring, and coaching. He is also a Fellow of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (FIA) and a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA).