Be careful with your surroundings

So much of our opinion of outcomes is related to the perspective from which we start.

We just listened to a presentation by our friends over at Trilogy Actuarial Solutions describing a new set of “modern deterministic scenarios” that could be implemented for performing Asset Adequacy Analysis through Cash Flow Testing.

The short of it is, Cash Flow Testing means the actuary certifies that under “moderately adverse scenarios”, the company has set aside enough money to pay claims in the future.

Now, for those uninformed, the previous industry standard to develop these “moderately adverse scenarios” for testing has long been the New York 7. The methodology for developing those scenarios hasn’t been updated since they were introduced decades ago. Heck, our Product Evangelist was running New York 7 scenarios as a fresh actuarial student in the early 2000s. Which means they’re probably a little stale. [“Probably” being a severe understatement.]

The scenarios still follow the same pattern – one Level interest rate scenario, a few “up” scenarios, and a few “down” scenarios, with some circuit breakers on each.

Some companies also create their own additional deterministic scenarios, with varying patterns: up-down-up-down, down-up-down-up, spike here and then fall below the original level, and so on. There might be 5, 10, or 20 additional scenarios used to evaluate outcomes assumed to be “moderately adverse” environments.

In addition, many companies run another 100 stochastic scenarios, to ensure that they are surveying a reasonably wide distribution of potential future paths. [Why 100, not 500 or 1,000? Partly because it used to take so long to run. Not any longer – hooray for new tech!]

The point is, you don’t know going in to each testing situation which scenarios would actually be “adverse”. You could make some predictions, based on previous testing, but until you get in and actually run the thing, you don’t really know.

Because “adverse” for one company, with a high exposure to callable bonds, might be a very different situation compared to another company in which duration mismatch is the biggest risk. And both would be still even more divergent from another company in which guaranteed interest on fixed deferred annuities are constraining free cash flow in years 20+.

“Adverse”, it turns out, is highly dependent on your perspective. Where you’re coming from. In other words, your “exposure” to the situation.

And now we come to today’s field trip into the world outside the actuarial department.

GameStop, WallStreetBets, and alternative investment vehicles

Over the past few months there has been a lot of noise in a Reddit subforum r/WallStreetBets about sticking it to the man. “The man” is loosely defined as institutional investors who have been shorting GameStop stock (and others) in a bid to profit from decreasing prices.

Here’s an Investopedia article on the topic.

And here’s a great summary of what’s going on, from Slate.

So on one side you have small retail investors (individuals, maybe a neighborhood investment club, something like that), investing $100, $10,000, maybe as much as $50,000 in an individual stock or position. On the other side you have retail investors, investing hundreds of millions of dollars or more in other positions, to leverage their influence and economies of scale.

There is no problem with doing that. Such investments make for interesting case studies in human psychology, high-frequency trading, and irrational decision-making.

On r/WallStreetBets, however, some “regular Joes” decided that they were tired of institutional exploitation for gain at their expense. They decided to band together and drive GameStop stock higher, to force those institutional investors to take losses on their short sales.

The funny thing is, it worked.

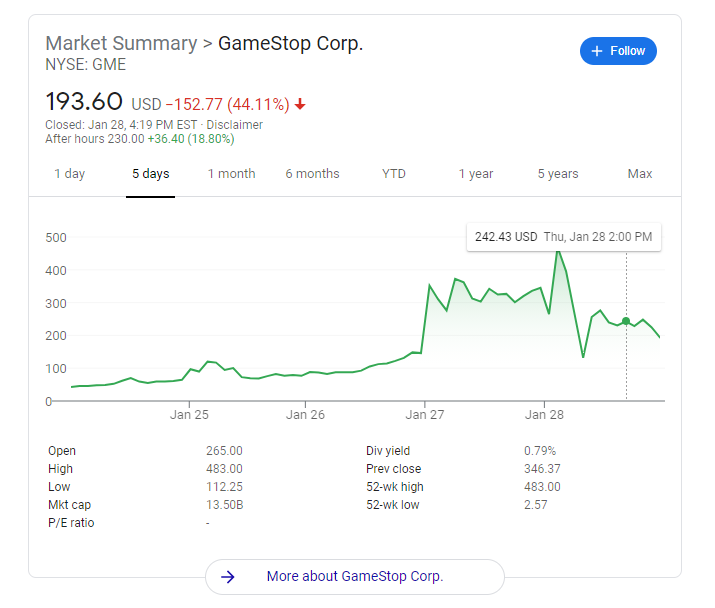

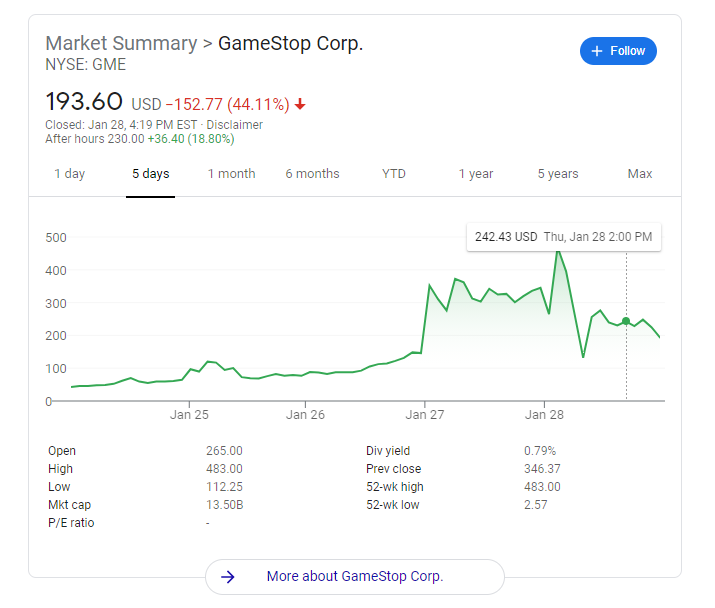

Now that the squeeze is on, GameStop stock has spiked in the last 2 weeks. Volatility is super-high, and not going anywhere any time soon. Trading has been halted multiple times in the last few days because of the volume going through.

From a stock price of under 5 at the end of August, 2020, to about 20 at the end of December, this week the price has skyrocketed.

Monday’s close was 77.

Tuesday: 148.

Wednesday: 348.

Thursday: 194 (after peaking as high as 483!!!).

So if you sold short shares at 20, like those institutional investors did, planning that the price would go down to 15, 10, or 5, and you’d make 33%, 100%, or 300% gains, well, it turns out you were just a little bit off. Anyone who covered their short positions on Wednesday would have lost about 95% of their value. On Thursday? Only 90%.

As a result, those short-sellers have taken massive losses, while a few of the little guys have made some correspondingly massive gains.

Ultimately, what this means is that some people are making a bundle (at least on paper), at the expense of some other people. It’s just that this time, the profits are flowing the opposite way they usually do.

[If you read this any time after the middle of February, 2021, all the fun is likely to have wrapped up weeks before. But the lesson will still apply.]

What this comes down to is perspective

The stock price went up. That’s just a fact. It’s a scenario. That fact in and of itself is neither “adverse” or “favorable”. What is “adverse” or “favorable” is your current position when that scenario unfolds, and how you react to it.

Short sellers view stock price increases as adverse. Long owners view price increases as favorable. Same action – different conclusions.

So – back to Asset Adequacy Testing. Specific scenarios applied during Cash Flow Testing should not be assumed to be “adverse”. The scenarios only offer potential situations. The unique company position (exposure, internal hedging, speed of adaptation, etc.) at the start of the scenario is what defines adversity – not the scenario itself.

Because if actuaries run the 16 Modern Deterministic Scenarios, be careful when examining aggregate results. Positive outcomes from some scenarios can cancel out negative outcomes from others. If you’re not careful, those offsets could lead you to think you’ve evaluated more moderately adverse scenarios than you really have. In fact, your run of 16 may have only actually given you insights into 2 or 3 adverse scenarios.

Sure, use the New York 7 or the Modern Deterministic Scenarios as a consistent baseline, but don’t stop there.

Why not run a whole bunch of stochastic scenarios too, and see which ones look moderately “adverse” to you, by your definition of adversity? Is it ending surplus? Is it intermediate surplus? Is it liquidity problems stemming from policyholder excess lapses somewhere between years 5 and 10? (It’s most likely ending surplus, so a good bet is to start with that).

Try to find some consistency between those. Are they all ones in which Treasury returns spike in the middle years? Are they all ones in which credit spreads widen very fast then shrink again? Are they differing by line of business?

Then, once there is an understanding of what makes those scenarios adverse, you can begin planning for some intervention, should you find yourself in the middle of one of those scenarios as it unfolds.

I.e., if you’ve shorted GameStop at 20, and the price is now 100 (some time Monday), it might be best to cut your losses and get out sooner rather than later. Remember, “The markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.” [Attributed to Keynes in the 1930s.]

Which means you’re probably going to have to do a lot of looking back at what you did three, five, or ten years ago, to see if the current environment is something like what you predicted might happen. [And so you’ll also need some good repositories and output data analysis tools to manage those data sets. SLOPE can help with that.]

The point is, we think that “adversity” or “advantageousness” is highly dependent on your current position and the adaptations you take as a situation develops.

Did anyone expect GME to spike starting last week? Probably not. But it’s a pretty good bet that those institutional funds that waited until Thursday to settle are wishing they’d acted sooner, on Monday, Tuesday. Even Wednesday, given the uncertainty of what might happen.

Their situation went from “moderately” to “significantly” adverse very quickly.

Yours could too, if you aren’t adequately prepared with the information you need to set plans in place and react when the time comes. You’ll do that by understanding that adversity is highly dependent on your perspective and exposure, not just the scenarios you run. Don’t get fooled thinking you’re adequately prepared when you’re really not.

And, by the way, buy sell do whatever you wish with your GME stocks or options. [We offer no advice, because we really don’t want to get sued on this one.]

If you’d like to see how to get stochastic results faster, consider SLOPE’s cloud-based, automatically-scalable platform. We can run 100, 1,000, or 10,000 scenarios in essentially the same time it takes to run 1. Want to see how? Schedule a demo.